The calling to provide pastoral care has led me to sit and listen to students share their stories of abuse and neglect and their related desire to find healing and hope. I have also sat in living rooms and church chapels as students "come out" to their parents and these same parents contemplate what it means to have a gay son.

I have met with families who are living paycheck to paycheck. I have listened to stories of students who wonder if their parents will ever get another paycheck.

Pastoral care is hard. Pastoral care is raw. Pastoral care is real.

Pastoral care is vital.

I did not always feel this way.

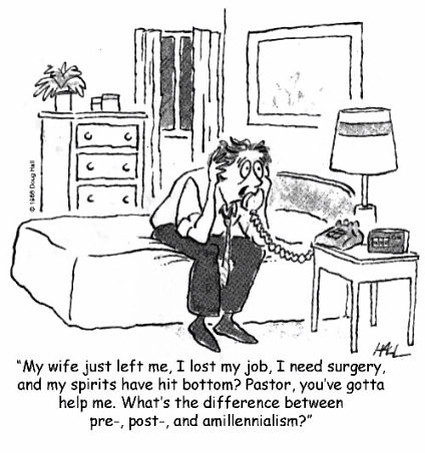

In the past, when I heard the term "pastoral care," I often thought of the church's attempt to provide its rendition of counseling by less than adequate and trained "counselors" (read: pastors). I had assumed that pastoral care was about providing members of a congregation with answers, advice, and solutions to help them heal and overcome obstacles. Even worse, pastoral care seemed as though it asked me to be who I was not- a therapist.

I preferred to think about theology, contemplate Scripture, and develop missional opportunities and partnerships locally and internationally. Pastor and teacher, I was. Counselor and therapist, I was not.

I was (and still am) convinced that what it meant to be the church was to participate in God's special concern for the poor, oppressed, and marginalized of this world. The church was called to carry the burdens of the abused and exploited, offended and rejected, wounded and forsaken.

This was all true.

Then I realized, this is the heart of pastoral care.

Pastoral care is this very opportunity to carry the burdens of others, especially those of the family of faith. When we engage in pastoral care, we sit alongside the weak and the wounded and share in their suffering, grief, sorrow, and loss."Bear one another’s burdens, and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ...So then, whenever we have an opportunity, let us work for the good of all, and especially for those of the family of faith" (Galatians 6:2,10).

The art of pastoral care should not be taken lightly. Pastoral care is a deeply theological discipline that bears witness to the incarnation and cross of Christ. Furthermore, when we practice pastoral care and extend solidarity to those who share their stories of pain and anguish, we live into what Luther called, theologia crucis, i.e. theology of the cross.

In Douglas John Hall's book, The Cross in Our Context: Jesus and the Suffering World, readers are reminded that we must hold in tension both the crucifixion and resurrection in theological reflection and missional praxis. That is, we can only begin to comprehend and bear witness to the good news of Jesus Christ by first apprehending the bad news that so often distorts the world and human experience. [1] When we begin to wrestle with the incarnation and crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth, i.e. theology of the cross, as God's entrance into the world's suffering and oppression, we cannot help but hear echoes of our call to do the same.

The death of God-incarnate reminds disciples of the Crucified One that as much as God bore the pains and anguish for the sake of the other, we are also to extend solidarity and compassion to one another no matter what the cost. This is why pastoral care is vital.

A theology of the cross and the art of pastoral care collide when we consider the passion of Christ as God's ultimate demonstration of compassion. Hall writes:

That is to say, when we note the cross as the fullest manifestation of God's "with-suffering" nature, a minister's extension of pastoral care assumes greater significance. Pastoral care becomes incarnations of mitleid."What we call sympathy or compassion...is in German Mitleid- literally, with-suffering. To feel compassion, deeply and sincerely, is to overcome the subject/object division; it is to suffer with the other...Etymologically, of course, the word compassion contains the same thrust as does the German Mitleid: com (with) + passio (suffering)" (22).

One (false) assumption is that pastoral care primarily serves to fix dysfunction and change circumstance. While this may occur on occasion, and we celebrate these moments, it would be naive to think for a moment that ministers are either capable or called primarily to be professional problem solvers. Instead, those who offer pastoral care practice the presence of the crucified Christ in the extension of compassion to another. Hall writes:

A theology of the cross refuses to remain within the friendly confines of academic towers or church offices and instead inaugurates a cruciform people who engage a suffering world."By definition, the theology of the cross is an applied theology. How in this world of the here and the now we are to perceive the presence of the crucified one, and how shall we translate that presence into words, and deeds- or sighs too deep for either? That is the question to which adherence to this theological tradition derives" (42).

A theology of the cross provokes God's people to ask prophetic questions, who are the suffering in my congregation? Who are the oppressed in my community? Who are the weak and wounded in my neighborhood? We then extend compassion and community to those people who bear the marks of Christ. We enter into contexts of suffering alongside our neighbors in need and offer pastoral care through demonstrations of empathy and solidarity.

Still more, pastoral care is not only about the provision of services funded through member's tithes and offerings made payable to the family of faith; instead, pastoral care extends into our care and concern for all the weak, wounded, and oppressed of the world.

Pastoral care was exercised when pastors throughout Germany drafted the Belhar Confession to condemn the heinous acts and propaganda of the Nazi regime.

Pastoral care was demonstrated when a black preacher from the south named Dr. King advocated for civil rights for all peoples in the 1960s.

Pastoral care was illustrated when a tiny Catholic nun, whom they called Mother, cared for the lepers in Calcutta.

Pastoral care is pursued when a church in Philadelphia transforms an old Presby church on the Avenue of the Arts into a house of refuge for marginalized urban citizens.

When I consider my own context and what it looks like to apply a theology of the cross through the medium of pastoral care, I am reminded of the faces both within the ministry I lead and the community and world in which I live.

I ponder how I can extend pastoral care to the student who is crumbling under the suburban pressure and myth of achievement.

I contemplate what it would look like to extend community to the homeless on High Street and the hungry on Market.

I consider how I can listen to the stories of those who are down and out at the bar after a WAKA kickball game and offer them an alternative narrative to the bottle and the flask.

I pray through fresh opportunities to incarnate the mitleid of Jesus alongside the bullied middle school student or the uninsured immigrant.

The church is called to be a community that enters into the suffering of others. We reject the quest for glory that may come in the form of dogmatic certainty, doctrinal systems, impressive buildings, expansive budgets, and elaborate programs. Instead, as Christians we embrace a theology of the cross that moves us as individuals and communities towards solidarity and compassion among those who are suffering in our local and global contexts. Hall says it best:

This sort of ecclesiology, underscored by a theology of the cross, has enabled me to reclaim a love for pastoral care. Actually, a theology of the cross has reminded me that my vocation as a disciple of Jesus calls me to extend a concern for all those who suffer in whatever context I live and serve."The point is: the suffering of the church is not the goal but the consequence of faith...The church is a community of suffering because it is a community whose eyes have been opened to the suffering that exists" (152).

God has a predilection for those who suffer. God has from the earliest beginnings (Exodus 3).

As one who confesses an allegiance to this very God and has been called to minister in the name of the crucified Jesus, I also find myself with the same predilection. Yet, for too long, I misunderstood pastoral care as that which took place in a church office turned therapist den. Now, I am rediscovering the sacred discipline as any opportunity to journey alongside any and all who suffer, as a reminder that they are never alone.

And they are never without hope.

A theology of the cross always leads to a theology of hope.

Some would even say it begins there. [2]

But that is for another day.

[Note]

[1] Hall says it better, "The disciple community formulates its articulation of good news only as it experiences and seeks to comprehend the bad news that is just at this moment oppressing God's beloved world" (59)

[2] Moltmann writes, "Eschatology means the doctrine of the Christian hope, which embraces both the object hoped for and also the hoped inspired by it. From first to last, and not merely in the epilogue, Christianity is eschatology, is hope, forward looking and forward moving, and therefore also revolutionizing and transforming the present" (Theology of Hope 16).